Words matter. For over 40 years, watchmaking jargon has used the term subcontractors to refer to suppliers. It is high time we started talking about core business and professional environment rather than subcontractors.

By Joël A. Grandjean

Over recent decades, since the recovery from the quartz crisis, watchmaking has seen a steady enhancement of its status. At least, as far as terminology is concerned.

From little hands to golden fingers

For example, factory workers once known as petites mains (‘little hands’) are now called doigts d’or (‘golden fingers’), motors have become calibres, while additional functions are known as complications. Then factories became manufactures, even though the manual work carried out in them has shrunk dramatically and their verticalisation of tasks is akin to assembly line work. As for the skills of artisans, they have been elevated to the rank of métiers d’art.

Surprisingly, at a time when industrialisation was in full swing and the industry was moving towards the production of ever larger volumes, marketing language became increasingly focused on luxury and local rootedness, generating legions of fans: after all, bucolic images of watchmaking farms out in the countryside and loupes fixed in watchmakers’ eyes are more alluring than the greasy oils of milling operations or the blackened fingers of polishers. Even today’s parents are more likely to approve of the renewed interest in watchmaking careers among their offspring. Yet not so long ago, people discouraged their children from doing this kind of job, and if they were reconciled to the idea it was often because the training was less expensive.

From shadow to light

As those familiar with the soft-industrial aisles of the EPHJ Show know, more and more enthusiasts and enlightened amateurs, collectors first and foremost, are making the trip to Palexpo Geneva to experience the initiatory privilege of taking a peek behind the curtain. And uncovering a technical skill here, a practical lighting idea there, or a highly personal emotional response. This is an ongoing phenomenon. The dream conveyed by brands has thus gradually acquired a ‘backstage’ dimension which is to watchmaking what jam sessions are to the Montreux Jazz Festival.

The trade show has become a festival of industry conviviality, where high-profile stars, very often the brands and their leaders, mingle with crowds of the industrious and the wealthy, volunteers and innovators – talented individuals working in the shadows, cultivating discretion, a sense of service, a love of what they do and a passion for ingenuity. And it is in this discreet setting – the EPHJ Show is still limited to around 20,000 professionals – that a real sense is acquired of the brilliance of these brands and their end products. As Vincent Daveau, a professional watchmaker and journalist, puts it: “EPHJ is the only show that looks intelligently at the future of the watch industry.”

Cultural dimension

The ultimate accolade is to be recognised by UNESCO, which has just inscribed the craftsmanship of mechanical watchmaking and art mechanics on its Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity. On 16 December 2020, after an 18-month procedure, cambouis (dirty watch oil) made its sudden entry into the pantheon of universal consciousness. But the real victory has been here in Switzerland: for the first time in its history in this country, watchmaking is seen as something cultural, and no longer just about economics or exports, since it was the Federal Office of Culture that sponsored the UNESCO nomination. About time too! At a geographical level, it is also the recognition of a particular arc of Switzerland, a distinct part of the country: a predominantly French-speaking corridor which, no longer imprisoned by its natural escarpments, can fully devote itself to projecting its global influence.

The watchmaking locomotive

The other distinctive feature of the watchmaking industry is that it is a leader, an embellisher and sometimes a borrower. It is first and foremost, at least here in Switzerland, a cutting-edge, reliable and powerful locomotive, to which high-precision wagons can easily be connected, those being the other microtechnology industries, most notably automotive, space, connector technology and of course medical technology, which EPHJ has been championing since its inception.

As for its ability to embellish, watchmaking allows other sectors, which may sometimes be held in less regard, to enhance their appeal and desirability. For example, being able to add a few watchmaking orders to its order book will boost the prestige of any company operating in another field. All of EPHJ’s more than 800 exhibitors – 90% of them SMEs – cross from one camp to the other, focusing on their obvious similarities in terms of both machinery and a talented and versatile workforce. And innovative processes, and even the most minor improvements, find a way to translate and adapt to other fields of application.

Two-way transfers

Just like the bidirectional rotor, a watchmaking component that enables the winding of an automatic watch by transforming its wearer’s movements into energy, technology transfers are a two-way process. The watch industry is therefore a borrower too, not least in the field of materials, where, as a low-volume consumer, it has no qualms about incorporating and adapting to its needs the advances and discoveries made in other sectors. In fact, it shops around on a regular basis.

Rose gold, for example, which has become the benchmark for good taste, comes from the dental industry. There are many such examples, punctuating the watch industry’s recent history, which has seen it survive some life-threatening crises. Crises that would have been easier to weather if companies had had a lifeline in the form of alternative markets. This has always been a concern among watchmakers, as exemplified by the entrepreneur Luc Tissot, who was the first to bring medtech to the Jura Arc when, back in 1978, he transformed a floor of his watch factory in Le Locle into a centre for manufacturing pacemakers.

Luc Tissot, the embodiment of the watch-medtech partnership

“The founding of Precimed and its collaboration with watch manufacturing are a perfect example of ‘shared value’ between two companies, Tissot and Precimed (editor’s note: the joint shareholders were Hoffman La Roche and Luc Tissot). So the know-how accumulated over decades in watchmaking spawned a chain of new products,” explains this great captain of industry who, having returned home, has recently acquired the Milus brand, a venture that he is combining with other successful endeavours through his foundation. A subsequent example was Medos, later J&J (1983), which developed a programmable valve for treating hydrocephalus, meaning that patients do not have to be operated on again when surgeons want to alter the pressure in their brain in order to prevent dementia. Here too, watchmaking skills were unquestionably an asset.

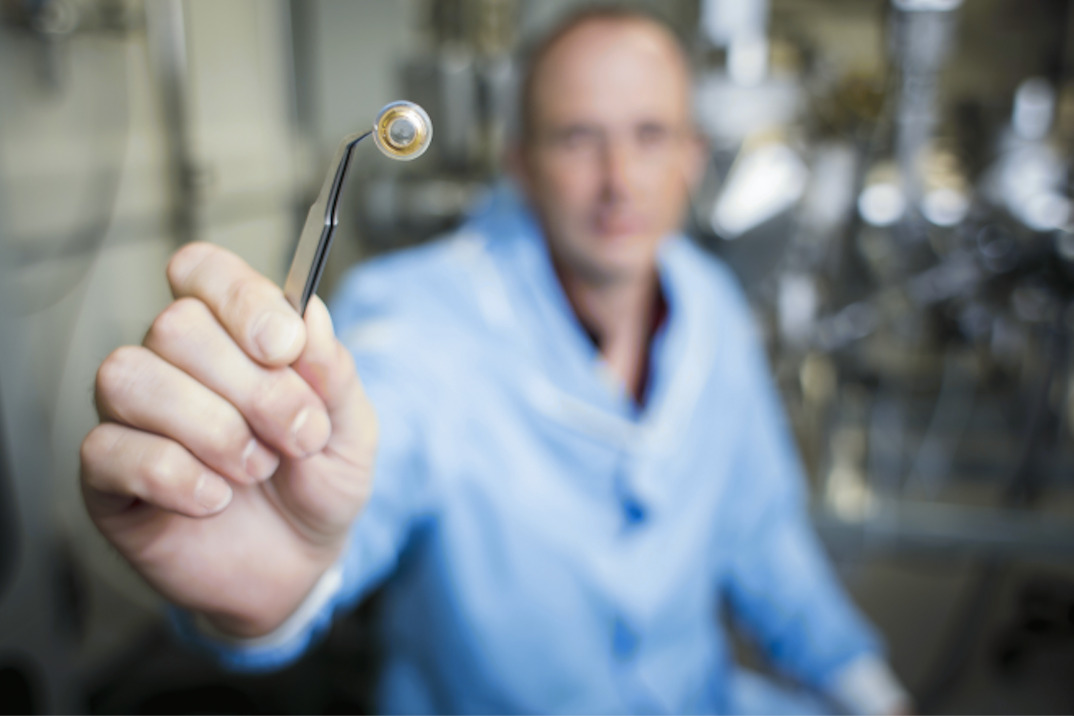

Then there is the project launched in 2010, and recently completed, a world first that was eight years in the making: having been approached by a Scottish university that had filed a patent for the continuous measurement of eye pressure, aimed at detecting the pressure surges that destroy the optic nerve and lead to blindness through glaucoma, the watchmaker is involved in the development of a smart lens (top photo). Let’s not forget that glaucoma is the second biggest cause of blindness in the world.

More recently, in the midst of the coronavirus crisis and just prior to its change of investor, the Acrotec Group announced at a press conference in Cortaillod that it had weathered the storm particularly well thanks to the diversification of its 20 or so companies. And it is not alone. Looking around at the world of watch co-contracting, as depicted in the columns of this newsletter for instance, examples of watch companies that have managed to break into other sectors have abounded during the pandemic. In La Chaux-de-Fonds, for example, AB Concept’s investment in a next-generation 3D machine has enabled Julien Bouchet to win customers in the automotive industry, among others.

Standards, a necessary step

However, the back and forth between watch companies and medical technology players is subject to some significant, though not insurmountable, barriers, including standards, materials, processes and packaging. Though it undoubtedly takes some effort, these barriers can be overcome. For example, when veteran company Pierhor-Gasser announced that it had obtained ISO 13485 certification after two years of effort, opening up many new possibilities by showing that the systems it uses to manage the quality and safety of its components for medical devices meet specific demanding criteria, it represented a very inspiring message of hope for the future of other businesses.

In fact, such a message has already been doing the rounds at EPHJ, ever since Switzerland’s largest annual trade event chose to open its doors to the medical technology industry. And also since it started awarding an annual Watch Medtech Innovation Challenge Prize at the show, in partnership with Fondation Inartisa, designed to boost and showcase the acceleration of these invaluable transfers.